Analysis, design, and problem-solving depend on pattern recognition. When organizations assemble a team of managers or designers to represent different business groups, each person brings the assumptions of their group culture and “best practices” with them. They are expected to collaborate as if they totally understand every single part of every business practice involved. But there are multiple, interrelated problems involved in any situation and different stakeholders will perceive different problems depending on their background, their experience of the business, and their place in the organization (what problems affect them). The key skill is to recognize those problems and tease them apart, dealing with each one separately.

Organizational problems – whether operational or strategic – typically span organizational boundaries, so the design of business processes and enterprise systems is complicated. Boundary-spanning systems of work need systemic methods and solutions. The point is to understand how collaboration works when people lack a shared context or understanding — and to use design approaches that support collaborative problem investigation, to increase the degree of shared understanding as the basis for consensus and action in organizational change. To enable collaborative visions, people need some point of intersection. In typical collaborations – for example a design group working on change requirements – the “shared vision” looks something like Figure 1.

Figure 1. Differences Between Individual, Shared, and Distributed Understanding In Boundary-Spanning Groups

The only really shared part of the group vision is the shaded area in the center. The rest is a mixture of partly-understood agreements and consensus that mean different things to different people, depending on their work background, their life experience, education, and the language they have learned to use. For example, accountants use the word “process” totally different to engineers. Psychologists use it to define a different concept from either group. When group members perceive that others are not buying in to the “obvious” consequences of a shared agreement, they think this is political behavior — when in fact, it most likely results from differences in how the situation and group agreements are interpreted.

Boundary-spanning collaboration is about maximizing the intersections of understanding using techniques such as developing shared representations and prototypes, to test and explore what group members mean by the requirements they suggested. It involves developing group relationships to allow group members to delegate areas of the design to someone they deem knowledgeable and trustworthy. It uses methods to “surface” assumptions and to expose differences in framing, in non-confrontational ways. But most of all, it involves processes to explore group definitions of the change problem, in tandem with emerging solutions. We have understood this for a long time: Enid Mumford, writing in the 1970s and 80s, discussed the importance of design approaches that involved those who worked in the situation, and the need to balance job design and satisfaction with the “bottom line interests” of IT system design (Mumford and Weir 1979; Mumford 2003) – also see Porra & Hirchheim (2007). This theme has been echoed by a succession of design process researchers: Horst Rittell (Rittel 1972; Rittel and Webber 1973), Peter Checkland (1999), and Stanford’s Design Thinking initiative (although “design thinking” tends to be co-opted to focus on “creativity” in interface design, rather than the integrative design approach that may have been envisioned).

The problem is that most collaboration methods for design of organizational and IT-related change employ a decompositional approach. Decomposition fails dramatically because of distributed sensemaking. Group members cannot just share what they know about the problem, because each of them is sensitized by their background and experience to see a different problem (or at least, different aspects of the problem), based on where they are in the organization. Goals for change evolve, as stakeholders piece together what they collectively know about the problem-situation — a process akin to assembling a jigsaw-puzzle. This is where boundaries become pertinent.

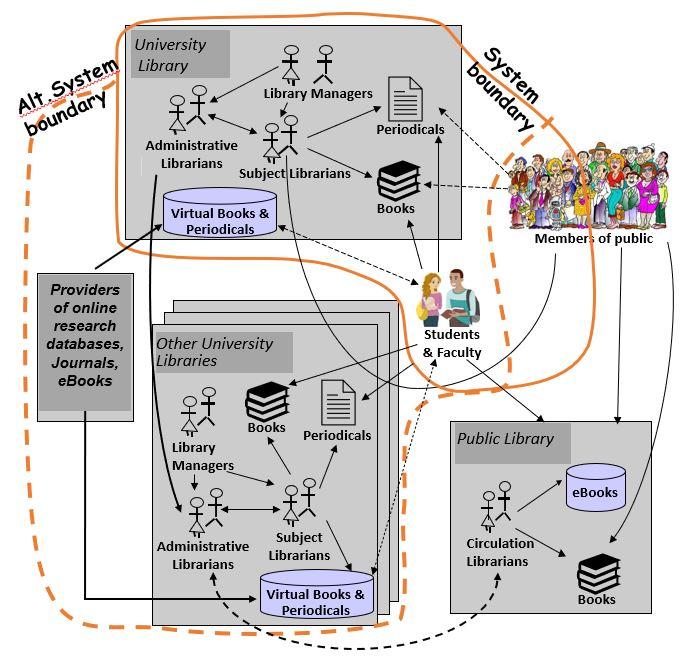

Figure 2 shows a (simplified) rich picture of the context in which a University library operates. If we wish to make changes to the library systems, there are a number of boundaries that we might consider:

- Services available to students and faculty within the physical University Library building. Books and periodicals (academic articles) are accessed by University students and faculty, both locally and remotely (by providing digital, online resources).

- The selection of the physical building may exclude wider access by members of the public. So we might extend the boundary to include selected members who pay a subscription fee, or who are eligible for membership because they live in the local area of the campus.

- However, a University Library cannot subscribe to every book and periodical in existence. Most University Libraries share the cost by making their resources available to other Universities through the Inter-Library Loan system. Including such loans (and virtual access) in the services we are supporting with our redesigned system or processes would need us to adopt an alternate system boundary that includes interactions with other University Libraries.

- Within the system boundary, we may need to include the providers or online resources: research databases, journals, and e-books. Otherwise, we cannot access the resources that we subscribe to.

- Finally, we probably need to maintain relationships with public libraries. These often provide access to a range of items – movies, popular magazines, popular fiction, etc. – that our students and faculty would want access to. We would probably need to provide reciprocal access to public library patrons in order for our students and faculty to obtain this access.

Figure 2. A Rich Picture Of The Context In Which A University Library Operates

The choice of a specific boundary is

- Functional: what processes or functions are included within the scope of change?

- Political: who has access to the system and why?

- Economic: how much does it cost to extend the boundary to other groups or departments, and what benefits do we obtain by doing so?

and - Pragmatic: how do we manage the diverse expectations and cultures of different groups or categories of user?

It is important not to just assume a specific boundary – boundaries are important and selecting too limited a boundary is a common problem in IT-related change where analysts are trained to focus on a single problem, with a simple boundary. Mapping out the scope and boundaries of the systems of work needing improvement is a key skill that analysts increasingly need to acquire. It is also important to recognize that boundaries require negotiation and facilitated communication across stakeholders. People in different parts of the organization see different problems – they fail to recognize that their problems are related to those of people in other parts of the organization. This can only be overcome by holding group workshops to explore these relationships.

Stakeholders for change often lack a common language for collaboration. They come from different functional groups, with different conventions used to represent problems. Facilitation of group processes is critical because (productive) conflict and explicit boundary negotiation tend to be avoided in boundary-spanning change groups. Misunderstandings are ascribed to political game-playing, rather than a lack of appreciation of the diverse business processes and functional groups that need to be spanned. To fix this, we need design and problem-solving approaches that support the distributed knowledge processes underpinning change and innovation — approaches that recognize and embrace problem emergence, boundary-negotiation, and the development of shared understanding.

References

Balcaitis, Ramunas 2019. What is Design Thinking? Empathize@IT https://empathizeit.com/what-is-design-thinking/. Accessed 8-15-2023.

Checkland, P. 1999. Systems Thinking Systems Practice: Includes a 30 Year Retrospective, (2nd. Edition ed.). Chichester UK: John Wiley & Sons.

[Original edition of this book published in 1981].

Mumford, E. 2003. Redesigning Human Systems. Hershey, PA: Idea Group.

Mumford, E. and Weir, M. 1979. Computer Systems in Work Design: The Ethics Method. New York NY: John Wiley.

Porra, J., & Hirschheim, R. 2007. A lifetime of theory and action on the ethical use of computers: A dialogue with Enid Mumford. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 8(9), 3.

Roumani, Nadia 2022. Integrative Design: A Practice to Tackle Complex Challenges, Stanford d.school on Medium, Accessed 8-15-2023.

Rittel, H.W.J. 1972. “Second Generation Design Methods,” DMG Occasional Paper 1. Reprinted in N. Cross (Ed.) 1984. Developments in Design Methodology, J. Wiley & Sons, Chichester: 317-327.

Rittel, H.W.J. and Webber, M.M. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences (4), pp. 155-169.