Why are systems changes counter-intuitive?

The human mind is not adapted to understand the consequences of a complex mental model of how things work. There are internal contradictions between future structures and future consequences, that become difficult to balance when multiple mental models are involved. Most people are “point thinkers” who only see part of the big picture. It is easy to misjudge the effects of change, when you only base your arguments on a subset of cause and effect. Systemic thinkers analyze interactions between various factors affecting a situation, to understand cycles of influence that affect our ability to intervene in changing the situation.

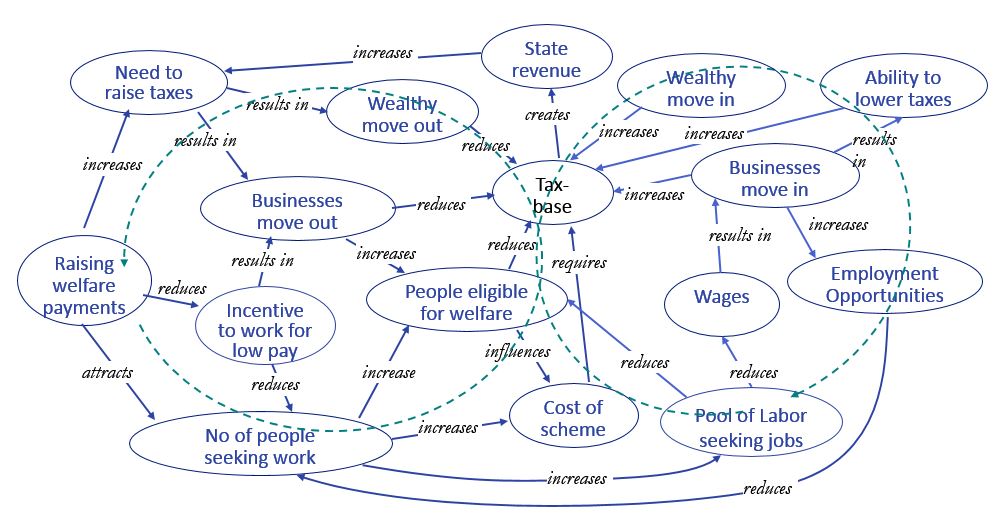

An example of two counter-intuitive sets of influences is shown in the “systemic” view of a state-run social welfare system, given in Figure 1.

We have two opposing “vicious cycles” of influence, in this model:

- The left-hand cycle reinforces the argument that raising welfare payments encourages “entitlement” and disincentivizes work.

- The right-hand cycle supports a counter argument, that raising welfare payments attracts job-seekers and increases employment, raising tax base revenue, to provide a net benefit (as well as humane assistance).

Unless a complete view of the whole system of interrelated processes is obtained, well-intentioned changes have unintended consequences. It is necessary to understand the system as a whole, rather than individual effects between factors, to understand these “vicious circles” of cause-and-effect. Tweaking one element will affect others, with knock-on effects as the two cycles interact. The only way to ensure a specific outcome is to intervene to break the cycle of influence (change the relationship between factors), or appreciate the interaction effects, so you can predict the outcome.

Typically, systems requirements analysis fails because of two reasons:

- The analysis is not sufficiently systemic – it reduces a complex system down to a subset of activities and work-goals that can be understood.

- The analysis is too focused on what can be computerized. It does not analyze what needs to change, but what the IT system should do to support an [implicit] set of changes.

Using Systems Thinking

We can start by analyzing the systems of human-activity: what people do to achieve various purposes in their work. The weakness with typical work or IT analysis methods is that these over-simplify the analysis, picking one business goal or individual purpose to focus on and attempting to merge in all the other purposes that people adopt when evaluating their work. For example, when I worked with a UK charity to evaluate their use of IT, I discovered that the managers administering the charity stores had multiple objectives, many of which conflicted in the detail of how they were achieved (the following is just a subset):

- To maximize income for the charity by selling goods through the charity stores – this is used for both UK and foreign charity assistance

- To ensure consistent pricing of goods, so customers did not complain

- To assist residents of poorer areas by ensuring a supply of reasonably-priced clothes, especially warm coats and footwear in winter, and cool workwear in summer (charity is most effectively supported at the source)

- To maximize donations of high-quality goods

- To minimize the handling cost of donated goods that are poor quality and cannot be sold

- To provide a community-oriented work environment in the stores and donation-sorting facilities

- To support projects in other countries that assist low-income communities by importing and selling hand-crafted goods.

It can be seen that objectives 1, 2, and 3 conflict. Maximizing income often meant differential pricing, so residents of affluent areas paid more, and residents of poorer areas could afford the clothes they needed. Low-quality or damaged clothes were often donated and cost the charity a lot of effort to dispose of, or sell to clothing recyclers, who would shed and recycle the fibers into new clothes or other products. Support of community development projects in low-income countries meant that the charity often had to subsidize imported craft goods. So this set of objectives required a lot of nuanced decision-making around pricing, distributing, and selling goods in the stores. There was no single algorithm that could be applied to guide the charity’s IT systems. In almost every case, the answer to “how do you decide how to do X” was “it depends … .”

There is no answer that frustrates system analysts more, as IT requirements are predicated on a single goal!

Soft Systems Analysis

Typically, we define a single goal that conflates the multiple, often conflicting, objectives of the system of organizational work. This complicates, rather than simplifies the design of work-systems, as it excludes support for the multiple other purposes that people aim for in their work. Many times, purposes conflict with each other (like a healthcare system aiming to both manage costs and optimize health improvement outcomes). We need to be nuanced in designing systems that balance support for various objectives. This nuanced design requires a systemic approach, where we consider what human-activities need to be performed for each outcome, before reconciling these with support for other change objectives. This requires a recursive (spiral) approach to design, where we periodically “complicate” our thinking – and then ask “so what do we do now, understanding this new information?”

To deal with nuanced decisions, and systems of work that have multiple, conflicting objectives, we can use Soft Systems Analysis. Soft Systems are related processes of human activity, divided up in ways that makes the processes within each subsystem appear to accomplish a single purpose.

By breaking up work processes in this way, we will end up with multiple systems that contain the same processes. Typically, systems analysts attempt to prioritize objectives, designing each process for one purpose of work. The whole point of thinking systemically is to hold these multiple purposes in mind, supporting the real-world conflicts that managers and others face in their day-to-day work by giving them the information they need to make nuanced decisions.

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) takes a divide-and-conquer approach to analyzing a problem-situation. We represent the problem-situation with as little extraneous structure as possible, as a set of interactions between people-doing-things.

- We separate the subsets of activity performed for an identifiable purpose

- We model each subset as an “ideal world” process-flow.

- Comparing each to the real world allows us to define actionable changes, which recognize organizational, political, and economic constraints.

- Finally, we prioritize the resultant changes, to produce a plan of action.

There is a more complete explanation of Soft Systems Analysis on my design website, ImprovisingDesign.com